AN HYMN TO JUNO

STATELY goddess,

Do

thou please,

Who are chief at marriages,

But to dress the bridal bed

When my love and I shall wed;

And a peacock proud shall be

Offered up by us to thee.

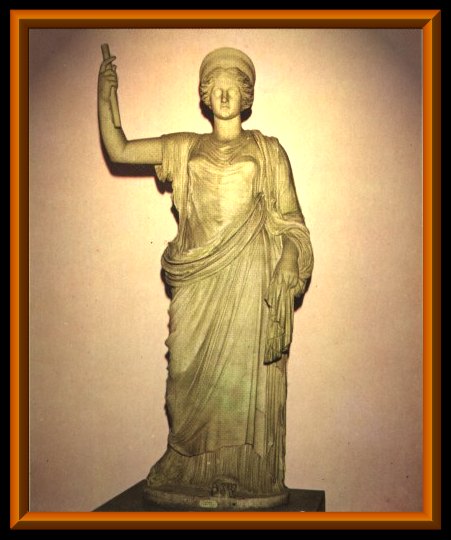

Juno was a very human-like Goddess to

the Romans -the ideal woman-citizen and icon of self-made prosperity; a

whole, integral, empowered, enlightened woman, committed to/a

revered influence in community, politics, money

management/business, marriage and motherhood, and a protector of

womanhood in all its natural power, beauty, and elegance.

Juno

is viewed as a guardian of womanhood: as every man had his “genius”

(literally “begetter”, guardian of manhood), every woman had her “iuno”.9

In Roman life, Juno watched over every aspect of women’s lives,

ensuring the continuity of the family12. As

such, her name changes with her role and each role has its holiday:

Juno Lucina, literally “Juno of light” watched over birthing, Juno

Covella guards the Calends with Janus,10 Juno

Sospita was literally “Juno the savior”, Juno Populonia blessed people

under arms, Juno Sispes was the protector of the state, Juno Sororia

protected girls at puberty, Juno Curitis protected spearmen.13

In the Roman territory of Treveri, Juno was even recognized as the

Iunones, the triple goddess.13 In similar

fashion, Juno Moneta was the “remembrancer”13

or “warner”, while Juno Regina was the Goddess of heaven and mother of

all15. It is in her form as Juno Regina that

she is most closely associated with her Greek equivalent, Hera9.

Indeed, in a number of myths, the names Juno and Hera can be used

interchangeably, as can Jupiter and Zeus, and many others.12

There is an important distinction between them, however; in general,

Romans viewed Juno and Jupiter in a kinder light than the Greeks did

Hera and Zeus.14, 16 In the story leading to

the birth of Mars (Ares), Zeus is renown for his rapes, and Hera, in

turn, for her jealous rages. Hera fought Zeus constantly from the

beginning, being tricked into becoming his wife. In contrast, the Roman

version of these stories is softer, casting Juno as more composed and

more determined to prove herself Jupiter’s equal: when Jupiter produces

Minerva from his mouth (without Juno), Juno conceives Mars with the

help of herbs from Flora12, emphasizing the

natural powers of womanhood, whereas Hera is portrayed as reactionary16.

Hera is routinely described as jealous whereas Juno is regarded as a

protectoress16. This is an important

distinction today to American women struggling for legitimacy: Hera’s

rage can be self-defeating whereas Juno’s composure and skilled

influence is empowering.

Our information on Juno comes primarily from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, 43BCE – 8AD, a piece which “ingeniously” wove various legends together, intentionally including the Greek epics3, thereby coalescing Juno and Hera, regardless of what either might have been before, and joined, teach a decidedly different lesson on womanhood than their original form represented. Juno retains her mother-goddess aspect even today; whereas Hera battles patriarchy from the position of second in command, her son becoming a representative of patriarchy, the God of War, Juno’s son, Mars, retains his ancient role as the mother-goddess’ ancient son13, the embodiment of the harvest, “conceived from her own lily” with the help of Flora, an image carried into Christianity in the immaculate conception and the angel Gabriel7. In truth, Juno’s roots are rooted in Etruscan beliefs.

A

matriarchal culture, the Etruscans inhabited the coast 90 miles West

of Rome, from the 7th to the 1st

centuries. Greeks, encountering Etruscan culture, claimed that Turan

was their most important Goddess, being a mother-goddess like the

Minoan Goddess, a being that was eventually disassembled by the Greeks

and scattered to their pantheon. Known Etruscan names for their deities

were Maris, Laran, Nortia (goddess of Volsinii city), Uni (Goddess of

Veii city, temple inscription, c.480BC), and Minerva (from c.500BC).

Greeks associated Uni with Hera but interestingly, gold foil for Uni’s

temple is inscribed with “Uni-Astarte”, (Phoenician translation of

Ishtar) suggesting an earlier Etruscan cultural association with Canaanites, Sumerians, Babylonians or Phoenicians, rather than with the

Greek pantheon.1 Etymological research closely

links Juno’s early latin name, Iuno, to Uni, who “consented” to be

removed to Rome when her city was conquered by the Romans in 396 BC, to

become Juno Aventine10, an idea supported by

the fact that early Roman deities were “numina”, faceless and formless;

anthropomorphization occurred under the influence of Greek and Etruscan

culture17. Interestingly, both Minerva and

Juno reappear together in the Capitoline trio along with Jupiter11,

who was paired with Juno as her brother and husband, in keeping with

the Greek pantheon’s matching of Hera and Zeus, Minerva taking on the

role of Athena15.1

Keeping

this background in mind, Roman culture was fiercely patriarchal.

Adultery was prohibited for women, but expected for men. A father had

strict control over his entire immediate family, including the right to

expose, kill, disown, sell, or emancipate his children, regardless of

their age, until his death. Women were generally excluded from public

life except as priestesses or unless they were closely related to a man

in power. Later in the Republic, women obtained greater freedom to

manage their own business and financial affairs, and own, inherit, or

dispose of property, unless they were married, still having no legal

right over children. Marriage and divorce was common and principally

required for the legitimacy of children, being marked only socially by

the passing of a dowry and the desire for a lasting union.13

There was no prescribed ceremony for marriage, excepting

conferreatio, a relatively uncommon and most sacred marriage requiring

the head of Roman religion to designate a priest to be present as a

cake of grain was cast into Vesta’s fire by the couple; divorce in this

case is almost impossible.13 This ceremony and

attitude toward marriage would become the standard with the advent of

Christianity, and Juno, the guardian of womanhood and marriage, and

(thereby) the guardian of state, would become the unspoken honorary.

Indeed, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, a “modern” cathedral built on the

original site of the Roman Capital, was built directly over the ruins

of a temple to Juno Moneta8.

Juno

retains a direct historical link and close resemblance to her original

mother-goddess form, remaining a strong, elegant goddess and guardian

of women, whose contributions to society are recognized as an absolute

necessity to the continuity of that society, despite patriarchy. Her

sacred geese warned the city that the Gauls were attacking in time for

the city to be defended10. Her temple has

honorably housed the state mint, the Roman standard measure of length (pes,

foot), and historical listings of Roman magistrates13.

She is still honored in the calendar we use today and is silently

invoked at every wedding ceremony that calls for flowers, occurs in

June (Junonius), contains (Vesta’s) wedding cake, or requires a

(pontifex) religious or legal magistrate to sanctify16.

Conflicts

in the management of money and property are commonly the foremost

problem experienced by most marriages today; Juno Moneta, the guardian

goddess of state, womanhood, and marriage, is as relevant now as then.

Invoke the spirit of Juno Moneta for her graceful independence,

strength, and influence the protection of marriage, seek her aid in

wedding preparations, and for her support throughout

You will need:

A

small handful of silvery coins (i.e. not pennies), a goose feather, red

wine or berry juice, a small clear bowl or glass of water about 1/3

full, a plate, tray, or other covering to protect surfaces from stains,

altar setting, or other tools normally used for a simple blessing

Cast

your circle and purify as you normally would, then, when you are ready,

speak or chant:

Guardian goddess of woman-kind, protect me in my future state,

As maiden, mother, crone, I am, accept this tribute for my fate,

In remembrance, your coin, I lay, oh, guardian of my womanhood,

Instill

in me your essence, pray; and guide me, through my woman’s blood.

Drop

a coin into the water each time you finish this chant until you have

dropped your last coin. For each coin, try to think of what guidance or

protection you ask of her and what part of Juno’s upright womanhood and

inner strength you already embody that you wish to celebrate: perhaps a

better ability to manage finances, estate, career, independence, help

renewing yourself as a mother, wife, or whole, capable woman, or

perhaps renewal/rejuvenation of the marital relationship? When you run

out of coins, add the wine/red juice to the water and meditate on the

coins in silence. Meditate on your answers and whisper your intent and

gratitude to the feather. When you are done, dip the tip of the feather

into the bowl and let it soak until the feather is stained.

Your

goose feather, sacred to the Goddess Juno Moneta carries your wishes;

keep it as a remembrance of her blessings for when you forget, give it

as a gift to another woman for when she forgets, cut the tip into a

quill pen so she can guide your personal pen in good faith, or release

it to a strong wind.

References

1. http://www.bigeye.com/sexeducation/etruscans.html, (28Jul04)

5. http://www.bartleby.com/65/li/LiviusAn.html (28Jul04)

6. http://www.freefoto.com/preview.jsp?id=01-09-22 (28Jul04)

7. http://www.moonspeaker.ca/Hera/juno.html (29Jul04)

9. “Juno”, Larousse World Mythology, Pierre Grimal, ed., Hamlyn Publishing, NY, (1965), p. 178

10. “Juno”, Encyclopedia of Religion, Mirea Eliade, ed., Macmillan Publishing, NY (1987), v.8, p.213

11. Grimal, Pierre; Basil Blackwell, “Juno”, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, (1986), p.243

12. Cotterell, Arthur, “Juno”, MacMillan Illustrated Encyclopedia of Myths and Legends, MacMillan

Publishing, (1989), p.113

13. Adkins, Lesley, and Roy A. Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, Oxford University Press, NY, (1994), p. 109, 263, 212, 265, 270, 274, 313, 339.

15. "Juno", Encyclopedia Mythica from Encyclopedia Mythica Online, http://www.pantheon.org/articles/j/juno.html, (08Sep04)

16. http://www.discoverthepath.com/gds-june.htm (08Sep04)

17. http://www.crystalinks.com/romegods.html#Juno (08Sep04)

18. Herrick, Robert, Works of Robert Herrick, Alfred Pollard, ed. London, Lawrence & Bullen, (1891), v. I, p. 178